What motivates me to write? I reflect on this each day, especially when I haven’t carved out the time to do so. The blank page calls to me. I’ve embraced the advice of setting specific goals, whether that’s a certain number of words or dedicating a set time to sit in front of the screen or with an open notebook. I have a charming, small secretary, perfectly arranged with the right lighting in a serene spot, with paper and pens ready in the drawers, intended to inspire my creativity. Sometimes, writing ideas disrupt my sleep, prompting me to rise and capture them, though I also trust that some ideas will shine brighter in the light of day.

Once the first draft of this piece was written, I discovered I was repeating myself, incorporating similar versions of my early interest (and success) in writing. How unoriginal is that? But, bear with me, the conclusion is significantly different. This is a continuation of my self-discovery, which is a stated purpose of my Third Act.–Remembering, Reviewing, Recovering.

I asked some female classmates at my fifty-year high school class reunion, “How close are you to being what you wanted to be when you grew up?” Every one of us was glad to be retired from whatever we had done for a living. Teachers, social workers, accountants, a nurse practitioner, an ordained minister, and one bitter divorcee who resented having had to work to support herself.

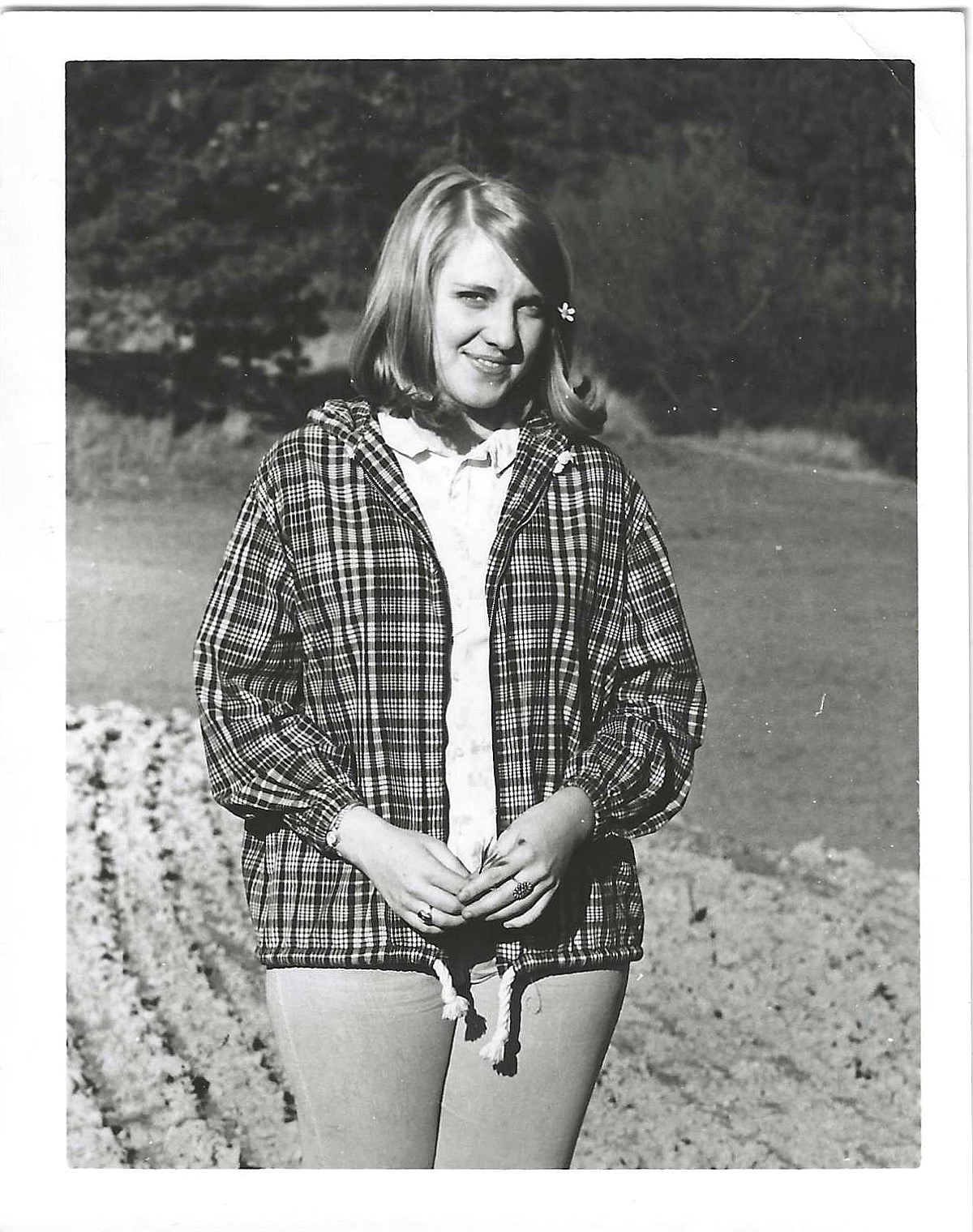

Much younger, when asked the question, “What do you want to be when you grow up,” I usually answered the question with the expected and acceptable, “I want to be a teacher.” In my heart, the answer was different; I wanted the life I saw my mother leading—raising kids, preparing meals for my husband, having time to read and sew, and playing bridge, gossiping with female friends, on a regular basis. The other, alternative answer, deeper within me, was “To be a writer.”

When I practiced the piano, I sat beside a wall of bookcases—collected mostly from the Book of the Month Club, a complete set of the World Book Encyclopedia, and collections of poetry (two of which I still own and visit frequently). If I wasn’t learning homemaking skills from my mother or doing the ironing, I was reading.

My first story was in print when I was seven years old. “The Washington Farmer” was a monthly magazine sent to our home. It included a section entitled: What Boys and Girls are Doing. I still have the paper dated June 7, 1956, that published my prize-winning story.

This is what I wrote:

“Once upon a time there was a sly old fox. In a nearby field there were some fine sheep. The fox wanted very much to gobble them up, but there was a jolly farmer who was proud of his fine sheep. Every night he had a good guard for them. But one night the guard fell fast asleep. When the fox saw that the guard was sleeping, he stole up on the fine sheep. He gobbled them all up.

In the morning the guard woke up and told the farmer all that had happened. The farmer caught the fox and put it in the zoo. He sent for some more fine sheep. He lived happily after.”

My punctuation skills were awkward, but my love for adjectives, especially “fine,” stood out. Winning the title of “Prize Winner” boosted my self-esteem and fueled my dream of becoming a writer, locking that desire in my heart.

All through high school, the diaries I kept related basketball scores, recounted the things I did after school and on weekends, included comments about the teachers and classes I liked the most, and kept a running commentary on boys I hoped would ask me out on dates. In college, I made daily notations in a desk calendar, describing which outfit I wore each day, vowing not to repeat the same outfit more than once every two weeks. Classes, coffee dates, movies, favorite music, and trips to the mall were carefully recorded. Outside of classwork, my writing endeavors focused on poetry, free-form verse filled with longing for love, hints of sensuality, and desire.

I learned the proper formatting for correspondence and followed it faithfully: date, a salutation/greeting, the body of information, a closing, and my signature. I often wrote to my two older sisters in college or beginning their families, sent friendly letters to friends I met at camp, and was always prompt with thank-you notes. Because my mother wrote to me each week I was in college, I expected her letter, and knew se expected a prompt response.

Over twenty-seven years in Pastoral Ministry, I honed my writing skills through sermon creation, newsletters, and newspaper columns, culminating in a dissertation. I embraced the alliterative mnemonic “Formation, Information, and Transformation” as my guiding framework, leading children and youth as their faith was shaped. By following the Biblical narrative in my preaching and teaching, I delivered precise information while actively working within church structures to transform the world into a more just and equitable place. My guiding principle was a deep understanding of the meta-narrative of scripture, which reveals the Creator’s intention for humankind to live in harmony with one another, with God, and with all creation. The powerful messages of love, justice, mercy, peace, and grace served as my unwavering touchstones.

When I retired, the personal journals I kept for thirty-five years had waited silently for me to rediscover my thoughts and feelings about the challenges of ministry, left as a sentinel between me and the page. I began to commit to writing, enrolling in writing classes, and over the first two years, I returned to the themes love, loss, despair and transformation in many of my pieces. What I had preached and taught and thought I was modeling for others, i realized was still held at bay, below the surface of professional facade.

In 2019, a Memorial Day Celebration in Springfield, Pennsylvania, honoring my first husband, who had died in Vietnam, opened the portal wider. The organizers of the event compiled a comprehensive biography of Bill Chandler’s twenty-four years of life. While others were able to capture his life through family and friends’ recollections, I accepted I had been unable to speak of my pain or tell our daughters about their father or my loss of innocence.

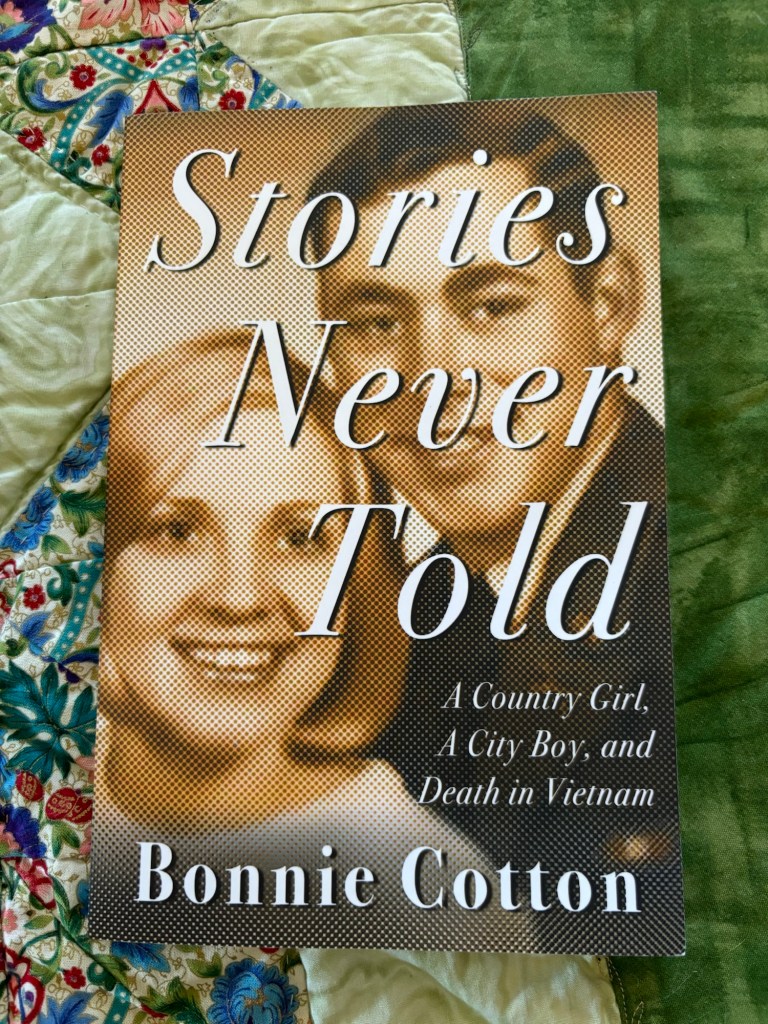

I began writing seriously, thinking I was doing so as my gift to them and their children, of knowing more about their father, explaining our love which brought them into being, and our brief life together. By the time the Memoir was completed, five years later, and even now, I understood why I needed to write it, and how it helped me, too. STORIES NEVER TOLD: A Country Girl, a City Boy, and Death in Vietnam, preserves a narrative of the complex events in my life between the ages of 18 and 24, and concludes with my reflections on how I coped, survived, and perservered.

And yet, it is about so much more.

I revisited treasured memories and embraced the sweetness of first love, brimming with hope. I acknowledged my dependency on the well-meaning guidance of my elders, understanding their desire for me to be brave, resilient, and to find the courage to truly live again. I became aware of the self-sabotaging patterns that had kept me from confronting my grief for five decades. I examined the roots of my perspectives and accepted the impacts of family dynamics. What I once studied, shared, and taught has transformed into something vibrant and deeply resonant within me.

The responses of others have helped—offering affirmations, sharing my grief, acknowledging the costs of war, speaking about the shared experiences of my generation—

My childhood friend admitted to discovering “things she did not know.”

My oldest daughter told me, “I understand you better now, why you did certain things.”

The most heartfelt description resonated deeply. I have written “A love letter on so many levels.”

I am a prize winner all over again.

I now recognize I write to understand myself and the world, to express what’s been unspoken, to reveal what’s hidden, to heal and provide healing, and, as Flannery O’Connor said, “to discover what I know.”

Leave a comment