Earlier this week, I gave a long-anticipated presentation on writing my Memoir. The audience was a medium-sized group of Seniors–all over fifty-five, and mostly in their seventies plus–which meets monthly for lunch. I approached the group facilitator last September, shortly after “Stories Never Told” was published. I was ready to promote it, certain that, being of similar age, many others had been impacted by the war in Vietnam. In the seven months that passed between September and April, my husband David also completed writing an autobiography, so it seemed fitting to speak about both books.

As I did throughout my preaching days, I outlined my remarks and incorporated questions that would lead to engagement in the subject and interaction among those present. My initial question was, “When you were 7 or 8, how did you answer the question, What do you want to be when you grow up?” There were answers typical of our generation–nurse, teacher, farmer–primarily occupations of our parents. One voice in the back added her grandson wanted to be a firefighter. I followed up with “How close are you to being what you wanted to be when you grew up?”

My personal answer to that question as a child was that I wanted to be a teacher, because admitting I wanted to stay at home, raise children, read books, play bridge, clean house, and sew as my mother had, seemed like an unacceptable answer. What I kept to myself was that I wanted to be an author, and have a book published by the Book-of-the-Month club. My first submission to “The Washington Farmer” was printed on the page entitled: What Boys and Girls are Doing. I was seven years old and clearly enamored with adjectives. The words “fine, very, jolly, and good” peppered my writing. My story called “The Sly Old Fox” was declared a prize winner. The sounds and meanings of words remained important to me.

I mentioned that my life has taken a circuitous route, from farm to college to marriage, to widowhood, back to college, raising kids and getting them in school, back to finishing my BA in Sociology, seventeen years after graduating from high school. Another three years of seminary education led to a career in pastoral ministry for twenty-seven years. Tack on another five years to complete a dissertation which earned me a Doctor of Ministry degree, and, not surprisingly, becoming a writer was long overdue.

When I asked my second question of the group, “What is your earliest memory? Where were you? How old were you?”, I eavesdropped on lively conversations around the tables. As I expected, they shared stories of maybe being three or four years old, and not being sure whether they remembered something as it happened, or as they had been told about it later.

I shared an illustration from Dave’s book, “Between Daylight and Darkness” because in the writing of his autobiography recounting having Polio as a child and a career in law enforcement he realized that his memory of learning to fish with his grandpa at the age of three was off by a year. Other events which led to his fishing experience could be dated by where he lived with his parents and when he went to visit his grandparents. That inaccurate dating of his first memory convinced him that his grandsons needed to be fishing at the age of three, and so they were.

I pointed out how the process of writing was useful to both of us, helping us clarify the effect of life events on our world-view; through our shared experiences and reflections, we were able to not only articulate our thoughts more effectively but also discover hidden patterns and insights about our beliefs. Dave was motivated by a book he received from his daughter titled “Tell Me About Your Life, Dad.” He discovered that answering the questions it asked in one or two line was not enough. Sentences became paragraphs, the paragraphs became chapters, the chapters turned into a book.

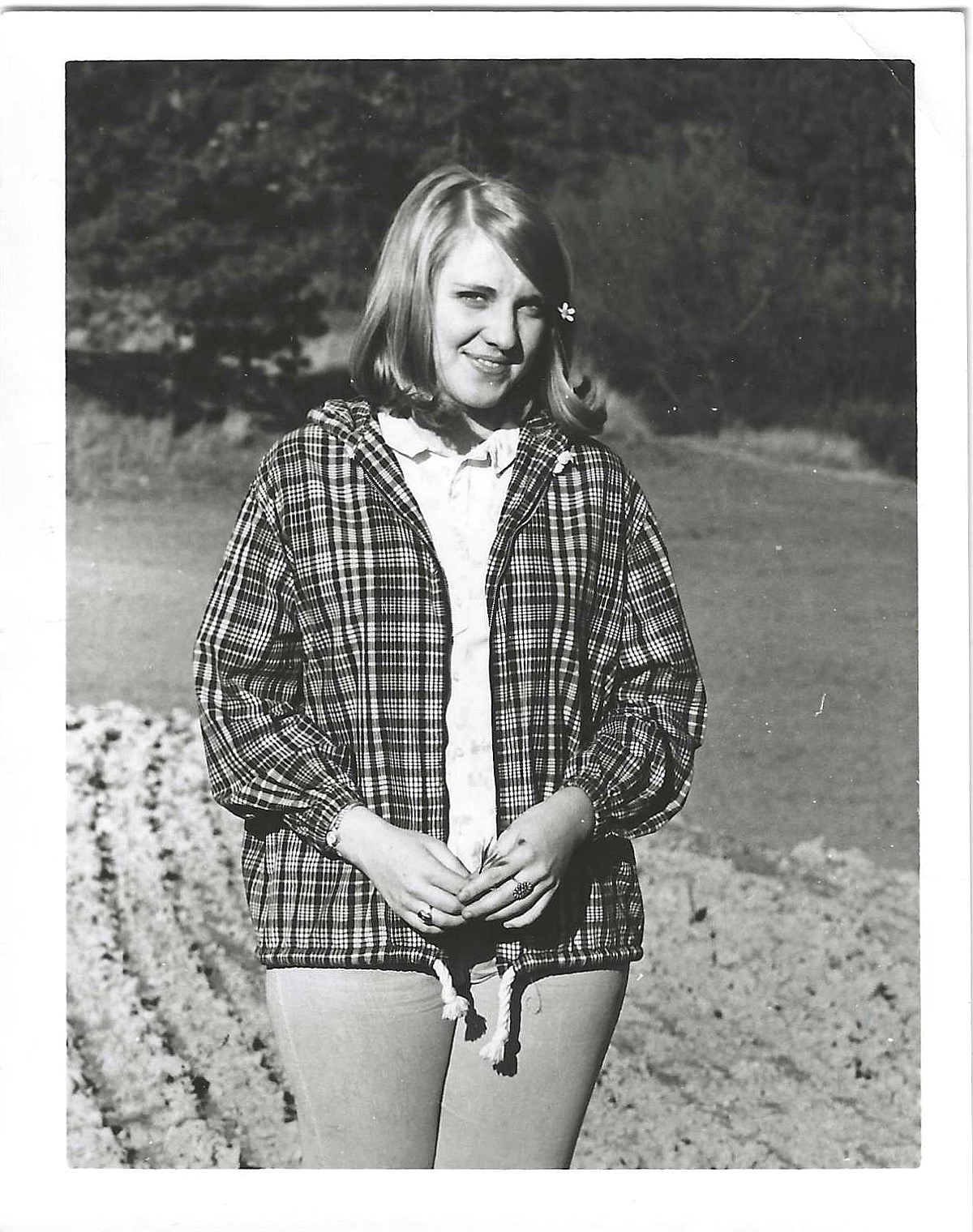

My motivation also came from a remark by my daughter, who was three months old when her father died in Vietnam. Traveling to Philadelphia in 2019 for a Memorial Day event honoring him, Abigail said, “I only know one story about my Dad.” Samantha, her older sister, adored her father, and because my memories of them together are so strong, I always believed she carried the same. Proofreading my text, she gently reminded me she was only three and a half, and has no memories except from the pictures she has seen. Correcting that oversight on my part and wanting to bring to life our love story, what I wrote is an intense narrative of a specific time, focused on events in my life between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four.

Those experiences shaped who I am today. This was not just a personal narrative but became a tapestry woven with threads of love, grief, and resilience.

My unique experiences shaped my anti-war views, reminding me that I shouldn’t generalize my generation’s perspective; just as American culture was divided over Vietnam, it remains politically fractured today.

I chose to read two passages–one with a humorous tone about how I met and fell in love with my first husband–and one in somber and reflective words from a letter written on the plane taking him to Vietnam for his first tour. It was a moment of self-promotion because our books were available to buy. I paused to ask for a show of hands from those whose lives were changed by Vietnam. Very Few responded.

Shocked by the silence, I remembered the motivation for having kept my story to myself for nearly fifty years, but knew the courage to write was minimal compared to the courage it had taken to live.

Leave a comment